Mohamed Mohamed OsmanBBC World Service, El-Obeid, Sudan

BBC

BBCTwins Makarem (left) and Ikram were in separate classrooms when the shelling began

It had been a normal day for 18-year-old twins Makarem and Ikram when their school came under fire.

Makarem was in an English literature class and Ikram was in a science lesson when they heard "strange sounds" coming from outside the school in Sudan.

Then the shelling started.

Makarem says her shoulder "tilted" as she was struck. Screaming, her classmates dropped to the floor to avoid shellfire and find somewhere to hide.

"We took cover beside the wall and the girl who was standing in front of me put her hand on my shoulder and said: 'Your shoulder is bleeding.'"

In the chaos, the two sisters, who had been in separate classrooms, tried to reach each other but couldn't. Later, Ikram searched for her sister, not knowing she'd already been taken to hospital.

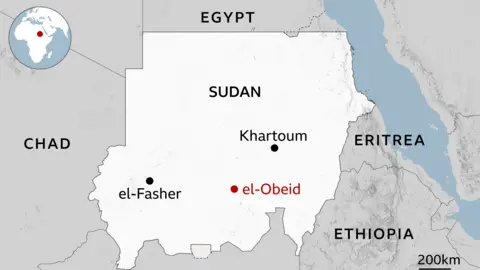

Like others who were injured, Makarem was taken to hospital by local residents who drove the wounded by car and animal-drawn carts because there was no ambulance service in el-Obeid, the city where they lived.

Eventually, her teachers and classmates had to convince Ikram to abandon the search and go home.

It was only when Makarem returned home from hospital later that day that her family found out she was still alive.

"I waited for her outside the front door and when I saw her coming we all cried," says Ikram, who had been in a part of the school that wasn't hit, so was unharmed.

The shelling left Makarem with a small piece of shrapnel in her head. It remains there more than a year later

Makarem and Ikram's English teacher and 13 classmates were killed and dozens more injured in the shelling at the Abu Sitta girls' school, in el-Obeid, in North Kordofan state, in August 2024. The school normally has about 300 students.

Regional authorities accuse the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) - the paramilitary group at war with the Sudanese army - of firing the shells.

The RSF has never commented on the incident and did not respond to the BBC's request for comment. It is not clear whether the shelling of the school was intentional.

Makarem says half of her friends at school were killed while the other half were injured.

As well as injuring her shoulder, she also suffered a head wound, but was discharged from hospital having received basic treatment.

But several days later, after developing severe headaches, she was given a CT scan which found a small piece of shrapnel in her head.

"It hurt very much and I had to take many painkillers," she says.

Sudan's civil war began in April 2023 and has resulted in the deaths of more than 150,000 people, with millions forced from their homes.

The United Nations says the country is now enduring the world's worst humanitarian crisis.

Sudan's oil-rich Kordofan region - which is divided into North, South and West Kordofan states - has become a major front line in the war due to its strategic significance, sitting between RSF-controlled areas in the west and eastern areas where the army is mostly in charge.

Analysts say whoever controls the region effectively controls the country's oil supply, as well as a large chunk of the country.

An estimated 13 million of the 17 million school-age children who have remained in Sudan are out of school, according to the UN.

North Darfur, under RSF control, is the worst affected state, according to the charity Save the Children, with just 3% of its schools open.

The Abu Sitta school was closed for three months after the attack while it was renovated.

Makarem and Ikram said initially they could not imagine returning to the place where their friends and teacher had been killed.

"But when I saw my friends returning and telling me that things were OK, I decided to return," says Ikram.

Even so, returning to school brought back painful memories.

"I used to close my eyes on the way to class to avoid looking at the area where the shelling happened," Ikram says.

A number of students were given psychological support at the school when they returned, says headteacher Iman Ahmed.

Beds and nurses were also made available at the school to allow injured students to take their exams in comfort.

Although el-Obeid is still being subjected to repeated drone attacks, students at the school were playing and laughing in the courtyard when the BBC visited in December.

The headteacher describes the girls' determination to continue their studies, despite what happened to them, "as a form of defiance and loyalty to those who were lost".

Ikram says she used to close her eyes on the way to class to avoid looking at the area where the shelling happened

But the situation for children trying to learn in el-Obeid remains challenging.

The city lived under a siege by the RSF for more than a year and a half, until the Sudanese army regained control in February 2025.

While there is now relative calm, dozens of schools have been converted into shelters for people fleeing the war.

El-Obeid hosts nearly one million displaced people across various shelters, according to the state's humanitarian aid commissioner.

Ibtisam Ali, a student at a secondary school that has been converted, says she cannot leave her classroom until the end of the school day because the grounds are full of displaced people.

"Even going to the bathroom has become a problem for us," she says.

Walid Mohamed Al-Hassan, the minister of education in North Kordofan state, said the presence of displaced families in schools had caused problems - including with sanitation - but that these are "the conditions of war and the cost of war".

The Abu Sitta school was closed for three months while renovations were carried out. Unlike some other schools in the city, it has not been converted into a shelter for people displaced by Sudan's civil war

In spite of the war and everything that has happened, Makarem and Ikram, who are now 19, are hopeful about their futures.

Ikram completed her studies at school and is now studying English at university in el-Obeid.

She was inspired by her English teacher, Fathiya Khalil Ibrahiem, who was killed in the attack.

The death of her friends made her even more determined to complete her studies, she says.

"I kept reminding myself that we should carry the same ambition to achieve what they were unable to achieve."

Makarem, meanwhile, wants to become a doctor like those who treated her after she was injured.

She passed her secondary school exams but did not achieve the score required to be admitted to study medicine at university.

Makarem says the shrapnel lodged in her head, which cannot be removed surgically, made it hard for her to study at first.

"I could only study for an hour and then rest for another hour. It was very difficult."

Dr Tarek Zobier, a neurologist in Sudan, said the medical implications of having shrapnel lodged in the head vary from case to case.

Some people will experience no symptoms and can live without medical intervention.

But if more severe symptoms, such as spasms, are experienced, surgery may be required.

For Makarem, the pain is no longer consistent, although it gets worse in winter when it's cold. She relies on painkillers when needed.

She's decided to repeat her school year so she can retake her exams.

"I believe that I will be able to achieve the score I am aiming for.

"I am hopeful for the future," she says.

Additional reporting by Salma Khattab

To support children in Sudan and other Arabic-speaking countries who are denied or restricted from accessing education, the BBC World Service is launching a new season of the Arabic edition of its award-winning educational programme Dars - or Lesson.

The first episode will air on Saturday 24 January, on BBC News Arabic TV. New episodes are broadcast weekly on Saturdays at 09:30 GMT (11:30 EET), with repeats on Sundays at 05:30 GMT (07:30 EET) and throughout the week.

The programme is also available on digital platforms, including BBC News Arabic YouTube.

More about the war in Sudan: