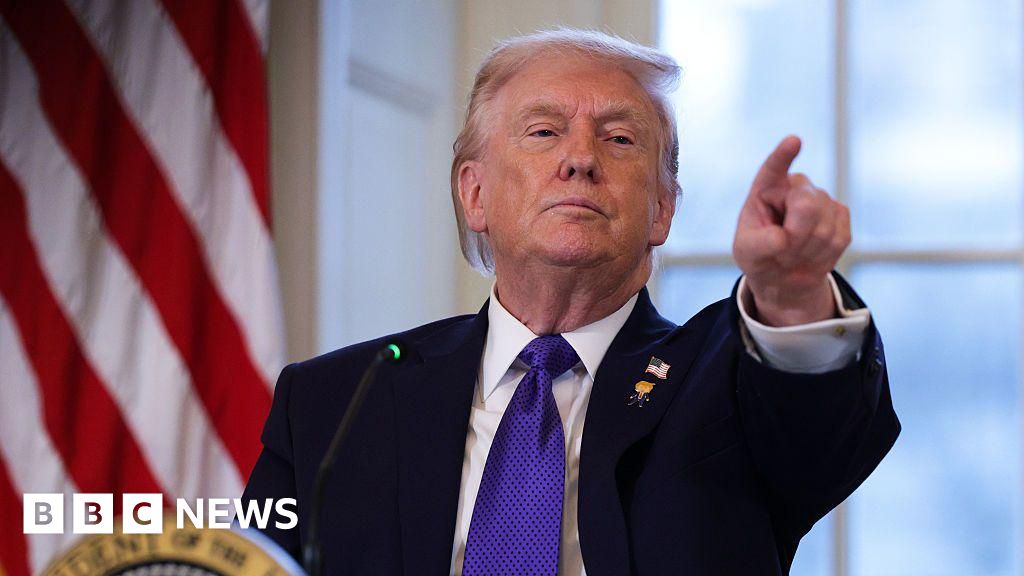

Getty Images

Getty ImagesChina's surging demand for durians is shaping South East Asia's farming towns

Driving around Raub, a small town in Malaysia, it's impossible to miss the prickly fruit that powers its economy.

You can smell it from the steady stream of trucks winding through mountain roads, leaving a faint fragrance on their trails.

You can see it too: the green spikes of a giant sculpture, murals painted fondly on low walls and road signs that proclaim: "Welcome to the home of Musang King durians."

A gold mining town in the 19th Century, Raub has seen its economy take on a new hue of yellow in recent years. Today it's better known as the land of the Musang King — a buttery, bittersweet variety that the Chinese have dubbed the "Hermès of durians", as prized as the French fashion house.

Raub is one of many South East Asian towns that sit at the heart of a global durian rush, pumped by China's growing demand. In 2024, China imported a record $7bn (£5.2bn) worth of durians — a three-fold increase from 2020. This is where more than 90% of the world's durian exports are now headed.

"Even if only 2% of Chinese people want to buy durians, that's more than enough business," says Chee Seng Wong, factory manager of Fresco Green, a durian exporter in Raub.

Wong recalls how farmers cut down durian trees to make room for oil palms, the country's main cash crop, during an economic downturn in the 1990s.

"Now it's the other way round. They're chopping oil palms to grow durians again."

BBC/Koh Ewe

BBC/Koh EweDurians are the pride of Raub

A very hungry China

With an aroma that has been likened to cabbage, sulphur and sewers — depending on who the nose belongs to — the durian packs a pungence so divisive that it's banned on some public transport and hotels. It has been maligned for gas leaks, and was the reason a plane was grounded after passengers remonstrated against the smell wafting from the cargo hold.

Fans from the region have christened it the "King of fruits", but on the internet it has earned a less flattering tag — the world's smelliest fruit — as tourists unused to its odour seek it out with squeamish curiosity.

Yet it has found a growing fanbase in China: as an exotic gift exchanged among the affluent; a status symbol to be unboxed on social media; and the star of culinary heresies from durian chicken hotpot to durian pizza.

Thailand and Vietnam are the top durian suppliers to China, accounting for nearly all of its imports. Malaysia's share of the market is sprouting fast, having earned a reputation with premium varieties such as the Musang King.

The average price of durian starts at less than $2 (£1.4) in South East Asia, where they are grown in abundance. But luxe versions like the Musang King could cost anywhere from $14 (£10) to $100 (£74) a pop, depending on their quality and the season's harvest.

"Once I ate Malaysian durian, my first thought was, 'Wow, this is delicious. I have to find a way to bring it to China'," says Xu Xin, who has been sampling durians at a shop in Raub. The 33-year-old sells the fruit back home in northeastern China, and is on the hunt for the best durians to import.

BBC/Koh Ewe

BBC/Koh EweVisitors to Raub are delighted with its durians

With her are two durian exporters from southern China, one of whom says business has been booming. The other expects it to continue: "There are so many people who haven't eaten it yet. The market potential is huge."

It's easy to see why they're so confident. Seated nearby is a large Chinese tour group — one of many that have been flocking to rural Malaysia for a bite of the fruit.

Eagerly they dig into platters of durian, carefully arranged from the mildest to the richest. If eaten in the right order, locals say, fresh notes should emerge with each glob on the flight: caramel, custard and finally, an almost alcoholic bitterness heralding the Musang King.

Such pedantry is perhaps why Malaysian durians have earned a special place on the Chinese table.

"Maybe in the beginning we only liked durians that were sweet. But now we look for things like fragrance, richness and nuanced flavours," Xu says. "Nowadays there are more customers who walk into the shop and ask, 'Are there any bitter ones in this batch?'"

BBC/Koh Ewe

BBC/Koh EweDurians arranged from mildest (top left) to richest, ending with the Musang King (bottom right)

Raub's durian dynasties

Just hours before the durians ended up on Xu's plate, they were painstakingly harvested at a nearby farm owned by Lu Yuee Thing.

Uncle Thing, as he's known in town, owns the durian shop, along with several farms. He is one of many success stories in Raub, where durians have made millionaires out of farmers. In family businesses like his, sons often help with transporting durians while daughters handle accounting and the finances.

"Durian has contributed a lot to the economy here," Uncle Thing says.

Driving to his farm one morning, there is quiet pride in his voice as he points out the Japanese pickup trucks that have replaced the rickety jeeps he used to rely on for transporting crates of his fruit.

BBC/Koh Ewe

BBC/Koh EweUncle Thing is one of Raub's big durian success stories

Still, farming is hard work. At 72, Uncle Thing wakes up at dawn every day and weaves around his hilly farm to collect ripened durians, either dangling from trees or nestling on nets close to the ground. A couple of years ago, a falling durian landed on his shoulder, leaving him with a throbbing pain that acts up now and then.

"It looks like farmers make easy money. But it's not easy," he says.

Once harvested, the durians are brought to Uncle Thing's shop, where they are sorted into baskets ranging from Grade A, for the large and round ones, to Grade C, the small and odd-shaped.

Sitting in the middle of the sorting floor is a lone basket reserved for Grade AA durians, the handsomest of the lot.

Those will soon be flown to China.

BBC/Koh Ewe

BBC/Koh EweThe daily haul at Uncle Thing's farm

A durian coup?

China's insatiable appetite for durians has shaped up to be a nifty diplomatic tool.

Beijing has signed a flurry of durian trade agreements, touting them as a celebration of bilateral ties — not just with major producers like Thailand, Vietnam and Malaysia, but also budding suppliers like Cambodia, Indonesia, Philippines and Laos.

"In this durian competition, everyone's a winner," declared a state media article in 2024.

The deals also dovetail with China's investments in infrastructure in the region. The China-Laos Railway, launched in 2021, now transports more than 2,000 tonnes of fruit every day, most of them Thai durians.

But this clamour to keep up with China's appetite comes at a cost.

Food safety concerns about Thai durians erupted last year, after Chinese authorities found in them a carcinogenic chemical dye believed to make the durians more yellow.

In Vietnam, many coffee farmers pivoted to durians, driving up global coffee prices that were already affected by severe weather.

And in Raub, a turf war has broken out. Authorities felled thousands of durian trees they said were planted illegally on state land. Farmers say they have been using the land for decades without any issue, and allege they are now being forced to pay a lease to continue farming there, or face eviction.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDurian trees and oil palms dominate Raub's landscape

Meanwhile, a coup may be on the way in China's island province of Hainan, where years of trial and error are bearing fruit. Its durian harvest for 2025 was expected to reach 2,000 tonnes.

Like in so many industries, from renewables to AI, China has long pushed to be self-sufficient in food too.

Even as it reaps the fruits of this durian diplomacy, it is eyeing what state media calls "durian freedom".

"For one thing, we won't have to rely on Thai and Vietnamese vendors when buying durians anymore!" proclaimed an article in August.

BBC/Koh Ewe

BBC/Koh EweCan Hainan unseat Raub in the durian supply chain?

That is still a distant dream. Hainan's first home-grown durians hit the market with much fanfare in 2023, but accounted for less than 1% of China's durian consumption that year.

But the way Uncle Thing sees it, "Hainan has already succeeded in its experiment... If they have their own supply and start importing less, our market will be affected."

He shrugs it off for now: "That is not something we can worry about. All that we can do is take good care of our farms and boost yields."

Ask anyone else in Raub about Hainan's quest, and your question will be swatted away with a smug comeback: they are still no match for Malaysian durians.

And yet, as China chases "durian freedom", it's hard to ignore the fact that the Musang King sits on an ever shakier throne.