Watch: 15-year-old Lulu tracks her social media use following the Australian ban

For the first time in years, Amy feels free.

One month since Australia's teen social media ban kicked in, she says she is "disconnected from my phone" and her daily routine has changed.

The 14-year-old first felt the pangs of online addiction in the days after the ban started.

"I knew that I was still unable to access Snapchat - however, from instinct, I still reached to open the app in the morning," she wrote on day two of the ban in a diary she kept for the first week afterwards.

By day four of the ban – when ten platforms including Facebook, Instagram and TikTok went dark for thousands of Australian children aged 16 and under – she had started to question the magnetic pull of Snapchat.

"While it's sad that I can't snap my friends, I can still text them on other platforms and I honestly feel kind of free knowing that I don't have to worry about doing my streaks anymore," Amy wrote.

Streaks - a Snapchat feature considered by some as highly addictive – require two people to send a "snap" – a photo or video – to each other every day in order to maintain their "streak" which can last for days, months, even years.

By day six, the allure of Snapchat - which she first downloaded when she was 12 and checks several times a day - was fading fast for Amy.

"I often used to call my friends on Snapchat after school, but because I am no longer able to, I went for a run," she wrote.

Fast forward a month, and her habits are markedly different.

"Previously, it was part of my routine to open Snapchat," the Sydney teen tells the BBC.

"Opening Snapchat would often lead to Instagram and then TikTok, which sometimes resulted in me losing track of time after being swept up by the algorithm ... I now reach for my phone less and mainly use it when I genuinely need to do something."

'It hasn't really changed anything'

Amy's experience is likely to put a smile on the face of Australia's Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, who in the lead-up to the ban pleaded with kids to kick their social media habits.

The government has cited online bullying and protecting young people from online predators and harmful content as some of the reasons for the ban.

Since 10 December, tech companies risk being fined up to A$49.5m (US$32m, £25m) if they don't take "reasonable steps" to boot under-16s off their platforms.

But Albanese's hopes that the ban would usher in a new generation of sports-loving, book-reading, instrument-playing kids may have fallen flat for many.

Aahil, 13, hasn't read more books, played more sports or started learning an instrument.

Instead, he spends about two and a half hours on various social media platforms every day – the same as before the ban started.

He still has his YouTube and Snapchat accounts – both use fake birthdays - and spends most of his time on gaming platform Roblox and Discord, a messaging platform popular with gamers – neither of which are banned.

"It hasn't really changed anything," Aahil says, as most of his friends still have active social media accounts.

But his mum Mau has noticed a change.

Supplied

SuppliedAahil, 13, spends more than two hours a day on social media, mainly playing games.

"He's moodier," she says, adding he spends more time playing video games than before.

"When he was on social media, he was more social … more talkative with us," Mau says, though, she adds, his moodiness may also simply be the "teenage years".

Consumer psychologist Christina Anthony says moods might be due to the ban's short-term effects on emotion regulation.

"For many teenagers, social media isn't just entertainment - it's a tool for managing boredom, stress, and social anxiety, and for seeking reassurance or connection," she says.

"When access is disrupted, some young people may initially experience irritability, restlessness, or a sense of social disconnection… not because the platform itself is essential, but because a familiar coping mechanism has been removed."

Over time, young people may adopt new coping strategies such as talking to trusted adults, she adds.

Snapchat's out, WhatsApp's in

In another Sydney household, the ban has had little impact.

"My usage of social media is the same as prior to the ban because I made new accounts for both TikTok and Instagram with ages above 16 years old," says 15-year-old Lulu.

The new law has influenced her in other ways.

"I am reading a bit more because I don't want to be on social media as much."

But she's not spending more times outdoors, nor is she arranging to meet friends face-to-face.

Instead, Lulu, along with Amy and Aahil, all started using WhatsApp and Facebook's Messenger more – neither are banned - because they couldn't contact friends who had lost access to their social media accounts.

This, Anthony says, goes to the heart of why social media is fun and engaging in the first place: it's social.

"The enjoyment doesn't come from scrolling alone, but from shared attention," she says, "knowing that friends are seeing the same posts, reacting to them, and participating in the same conversations."

When that "emotional lift" fades, the platform begins to feel "oddly unsocial".

"That's why some young people disengage even if they technically still have access…without peers present, both the social feedback and the mood payoff drop sharply."

Kids flock to apps as FOMO sets in

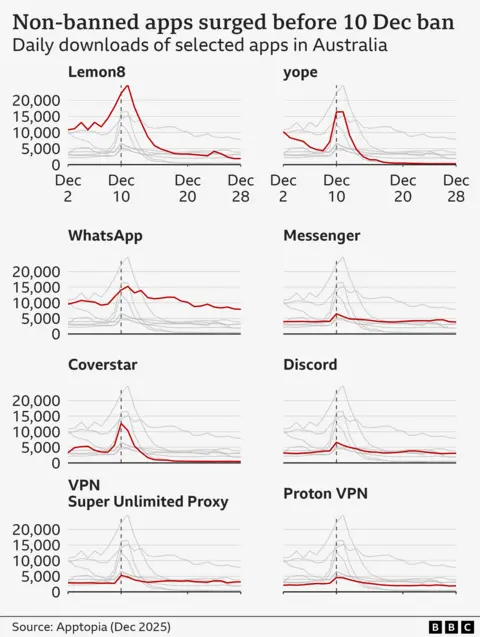

Seeking lookalike apps to fill the void was exactly what thousands of Australians did in the days before the ban started, with three little-known apps - Lemon8, Yope and Coverstar - surging in downloads.

This attraction to alternative photo and video-sharing platforms fits into what's known as compensatory behaviour, Anthony says.

"When a familiar and emotionally rewarding activity is restricted, people don't simply stop seeking that reward… they look for alternative ways to get it," she says.

"For teens, that often means compensating with platforms or activities that provide similar psychological benefits: social connection, identity expression, entertainment, or escapism."

That initial rise has now dropped but daily downloads are still higher than usual, says Adam Blacker from Apptopia, a US-based company which tracks consumer trends of mobile apps.

The fall in downloads suggested "a chunk of kids might be embracing the new rules and swapping their time spent on mobile for time spent elsewhere," Blacker says.

Amy was one of the thousands who downloaded Lemon8 - created by the makers behind TikTok - before the ban.

"This was largely influenced by social pressure and a fear of missing out as many people around me were doing the same," she says.

But she has never used it.

"Since then, my interest in social media has decreased significantly, and I don't feel any need to download or use alternative platforms."

The number of Australians downloading virtual private networks – or VPNs – also increased before the ban, but has since fallen back to normal levels.

VPN technology allows users to hide their location and pretend they are based in another country, in effect, bypassing local laws.

But they have limited appeal to teens, Blacker says, because many social media platforms can detect VPNs.

"Teens can only leverage VPNs to create a new account," he says, so "they would be starting over in terms of connections, settings, photos and more".

Gaming 'much harder to get into'

In the months before the ban, debate swirled around the exclusion of gaming platforms, with critics concerned that many youngsters use them in the same way as social media, meaning they presented the same types of potential harms.

While there's no evidence yet on whether more teenagers have switched to the likes of Roblox, Discord and Minecraft to socialise, it's a real possibility, says Mark Johnson, an expert in gaming live stream platforms such as Twitch, which is part of the ban.

"But that's also contingent on a young person having the required hardware, the required cultural and technical knowledge, and so forth - games are much harder to get into, for the uninitiated, than social media sites," he says.

Johnson, who lectures in digital cultures at the University of Sydney, says the reaction to the ban has been mixed.

"A lot of parents seem to be reassured and pleased that their children and teenagers are spending far less time in social media," he says.

"Equally, some are lamenting the newfound difficulty their young people are having in communicating with their friends, and in some cases with family members who live elsewhere."

A spokesperson for the eSafety Commissioner says they will release their findings on how the ban is going - including the number of accounts that have been deactivated since 10 December - in the coming weeks.

Meanwhile, a spokesperson for the Communications Minister Anika Wells says the ban is "making a real difference" and leaders across the globe are looking to mirror the Australian model.

"Delaying access to social media is giving young Australians three more years to build their community and identity offline, starting with spending more time with family and friends over the summer holidays," the spokesperson says.

Time will tell

Supplied

SuppliedReading, crocheting and exercising are some of the activities Amy, 14, is doing more of since the ban.

For Amy, one of the unforeseen benefits came in the hours after the Bondi Beach shootings on 14 December when two gunmen killed 15 people and injured dozens at an event marking the Jewish celebration Hanukkah.

"After the Bondi Beach incident, I was glad that I had not spent too long on TikTok, as I would have likely been exposed to an overwhelming amount of negative information and potentially disturbing content," she wrote on 15 December.

She says her time spent on social media has halved since the ban and while TikTok and Instagram are still fun, not having Snapchat has been a gamechanger.

"Snapchat gives me the most notifications so that's usually what gets me on my phone and then everything happens after that," she says.

For Amy's mum Yuko, she's noticed her daughter seems content spending more time by herself.

"We're not entirely sure whether this shift is directly because of the ban or simply part of having a quieter holiday period," she says, with most Australian students on school holidays until the end of January.

"It's hard to say yet whether [the ban] will be a positive or negative change - only time will tell."